Heraldry – a study of armorial bearings – has an ancient origin deeply rooted in biology. All living organisms have a genetically coded order for extraction of food and protection of living space. It is realized either passively, like in case of plants or fish, through carefree fertility, or through designation of territory, scaring away or discouraging competitors. Well known is the habit of lions to leave a characteristic smell of excreta to indicate the boundaries of their territory or sound announcements by nightingales claiming ownership of part of a grove or a park. In a society, one of the many ways to confirm ownership is to use a sign of the owner – a ruler, a clan or just a private owner. Such signs used to be laid stones, notches on rocks, trees, stamps burned on the skin of animals. They were also used by primitive tribes, then burghers, artisans, bee keepers, and put on seals of feudal lords. And it was those unique notches, dashes and pictures designed by a particular owner that became a prototype of the future coat of arms.

In times of emergence of medieval states, the elite of the society was chivalry – family groups that owned their own territories and had obligations to the ruler (prince) to provide an armed unit and participate in battles. The core of such a unit – a kin war banner – were knights, heavily armored, fighting with swords, spears and axes, sitting on strong horses and belonging to one family. Since the face of a knight was partially or even completely covered with a helmet, to distinct one from another they used sound signals such as a call, a family motto, a battle cry, as well as visual signs – a banner with a coat of arms as well as colors and coat of arms depicted on garments, helmets and shields. In addition to knights, a unit consisted of mounted crossbowmen, foot archers, squires and servants – also bearing heraldic colours.

In the midst of a battle, it was important to have a clear distinction of friends and foes. Identification of soldiers was so important that it was necessary to treat the matter with all seriousness and thoroughness. Ownership signs of drawn dashes were no longer enough. Signs in contrasting colors and in concrete, recognizable forms appeared on weapons and war banners. Like cats buckle their backs and bristle up to intimidate their foes, knights placed intimidating decorations on their helmets, which made them visually higher and fiercer, frightened enemy horses, and also made them visible from afar. Similar to visual signs, distinctive voice signs, or appeals, were, like coats of arms, attributed to particular military units.

Knights were the elite of the state, a prince or a king chose his officials, generals and judges from among them. Only they, except for the Church and the monarch, had the right to own land. They represented a closed and solidified social group aware of its own superiority, exclusiveness and strength. They had a sense of pride and dignity, and in battles observed the knightly code. Within several hundred years, knights received all possible privileges, starting from extraordinary tax exceptions, to a monopoly on clergy posts, to having their own legal proceedings, exemption from customs duties, and, finally, to liberum veto and the right to elect kings.

In the Polish Crown and the Grand Duchy of Litva *, there were three ways to obtain a status of nobility (i.e. Polish-Litvan šlachta or szlachta): adoption, ennoblement and indigenat (from the French indigénat).

Adoption was a recognition of a non-nobleman as a member of a noble family that gave him their coat of arms. The famous group adoption took place in 1413 as a result of the Gorodel Union, when the most influential Polish families granted their coats of arms to Litvan magnates. However, it was most common to adopt close friends, workers who had shown their worth in service, faithful and loyal subjects, combat companions, and sometimes wealthy middle-class men. Adoption became so widespread that in 1633 it was completely banned.

Up until 1578 ennoblement, that is, granting of an unique coat of arms and knighthood, was performed by the King (the Grand Duke) himself, after that it was done by the King under control of the Sojm, and finally, from 1601, by the Sojm, that is, by nobility brotherhood itself through their representatives.

Indigenat was an addition by the King and the Sojm of a foreign nobleman to the nobility and recognition of his coat of arms as Polish. Indigenat was a rarity in the Rzeczpospolita, in its history it was granted just a little more than 400 times. In addition to appropriate merits, a candidate was required to take an oath of allegiance to the Rzeczpospolita.

Unlike other European states, a coat of arms and other privileges were granted not to a particular person, but to the entire family forever. Inheritance greatly increased the number of nobility estate. In the 18th century, it accounted for almost 10 per cent of the population, which was several times more than in other European countries. At the same time, there was a great economic stratification, from great landlord to impoverished nobility without land and income leading a miserable life in towns or in the service of powerful gentlemen. However, in 1505-1775 the nobility was prohibited to trade or to be craftsmen under threat of deprivation of nobility.

A coat of arms indicated continuity of a family line and membership of a privileged class. There were no surnames in medieval Poland and the Grand Duchy of Litva, instead a combination of a name, place of origin and coat of arms were used, for example, Jan of Lyčki of Sulima coat of arms. Over time, this form turned into the family name of Lyčkovski and corresponded to the owners of Lyčki. When descendants of Jan came into possession of other estates, adopted their names as surnames; for example, Barkoŭski was derived from Barki, Rahačeŭski from Rahačy, Pryłucki from Pryłuki. Despite the different surnames, they all belonged to the Sulima coat of arms and were members of the same kin. Therefore, sometimes a single coat of arms refers to several hundred surnames of noble families creating a gigantic heraldic family, with a small degree of kinship or without it, but having a common family root back in ancient times and calling each other crest brothers. Since noble surnames were often of topographic origin, and less often came from nicknames, they could multiply as many times as there were villages of the same name, for example, Kukli, Dzieržany, Jaryčy, Hai, etc. Sons of one father could (and that often happened) have different surnames derived from the names of their estates. A man could also changed his surname when changing his estate. At times the byname (prydomak) became a surname, but a coat of arms remained the same.

A coat of arms, as a family identification mark, required legal protection of the state. Everywhere outside the Rzeczpospolita specific institutions, usually heralds offices, served this purpose. They kept registry of coat of arms including their images and descriptions, as well as names of their owners, the so called heraldic scrolls. An official of a herald office – a herald – checked, for example during tournaments, if coats of arms were used correctly and legally. They were royal institutions, therefore they had a high rank and authority. Herald offices still exist in monarchies. Polish kings made an unforgivable mistake – they did not create a royal institution that would register ennoblements and indigenats, and collect images of coats of arms along with the surnames of those families to whom coats of arms belong. As a consequence, the Polish-Litvan heraldry is in a dreadful condition. Images of thousands of coats of arms are unknown. Thousands of noble families do not know their coats of arms. The noble origin often was and is being proved only indirectly, for example, by high posts and performance of honorable functions by ancestors, possession of estates, participation in the Sojm and local sojmik, documents in which a family name or a surname was written with a noble title (generosus, nobiles, urodzony), seals or officer’s diplomas. An intact legal act of ennoblement is a true rarity. It was quite common to try to restore a forgotten coat of arms based on survived handwritten texts, inprints of seal rings (signets) on old documents, church paintings and tombstone sculptures. The quality of such reconstruction depended on skills of a provincial and often poorly educated artisan from a distant past.

Nobility in Poland, and – after a union with the Grand Duchy of Litva – in the Commonwealth, or, as it’s customary being called, though not officially, in Šlachta Republic, was closely and inseparably connected with possession of land, i.e. with economy, manor. Exceptions to these rules were rare, related to the latest wave of nobility and clearly indicated in ennoblement documents. The most important proof of noble origin of the family was a long-standing conviction of the neighbors in this fact, reinforced by numerous blood relationships of all families of the land. A citizen’s anonymity (protection of personal data), so cherished and protected nowadays, would make a person an outcast in circles of respectful lot and make it impossible for him to run a public, political, and, not unusually, even a management career.

The Polish system of inheritance of the nobility entailed division of the parental inheritance among all children. As a result, once huge allotments after several centuries turned into scraps of fields. These lands were not sufficient to support a big family, or acquire an adequate education or funds to buy tools, to maintain and enjoy many expensive elements of the nobility lifestyle. The memory of the noble lineage was carefully preserved, albeit severely curtailed, primarily, if not exclusively, in rural areas where the situation of neighbors was similar, thus it cost them little to protect their collective identity.

Unlike neighbors’ recognition, other proofs of nobility (such as documents, coats of arms, signets) were considered secondary, and sometimes simply superfluous. Therefore, after the occupation, during the legitimation procedures, when nobility members were required to provide their long-forgotten coats of arms, many without any confusion or embarrassment drew them in a rather arbitrary manner, seeing no guilt in doing so and, to the contrary, recognizing their actions as morally justified neglect and sabotage of the demands of the occupiers. Many diplomas issued by the Russian Tsar royal herald office confirming nobility contain unknown coats of arms, which have nothing to do with really existed images, and it is very unlikely they will ever be found.

The absence of a state institution responsible for heraldic control led to rather wide and unrestricted use of coats of arms. As noted, strictly observed and controlled, first of all on a social level, was only the very fact of noble origin. Its external manifestations became gradually ignored when ownership of a surname became normal. There were instances of unauthorized alterations of coats of arms, by changing appearance and color or using additions and deletions. Most often those alterations were of minor nature caused by desire to single out one family that belonged to the same coat of arms from another one living in close proximity, or to distinguish an isolated group that had settled in a remote part of the Commonwealth. Such a change, nowhere affirmed or described, led to creation of new variation of a particular coat of arms, often named after the name of its owner. This phenomenon did not break the original kinship unity, but multiplied the number of coats of arms. However, with years, this original linkage was vanishing.

There were about 200 main coats of arms, by adding different variations this number increases to over 5 thousands, known and unknown, forgotten or known partially, for example, missing colours or crests. The function of herald offices and official heraldic scrolls was assumed by authors of Armorials, historians and enthusiasts. The first Polish armorial is the late 15th century Insignia seu clenodia Regni Poloniae by Jan Długosz consisting of 139 coats of arms with their descriptions and images. Analysis of other sources shows that Długosz described only a small portion of contemporary coats of arms. In the 16th century two armorials, Gniazdo cnoty (The Nest of Virtue) and Herby rycerstwa polskiego (The Coats of Arms of the Polish chivalry) by Bartosz Paprocki, were published. The armorials compiled by priest Kasper Niesiecki in mid-18th century and Adam Boniecki in late 19th – early 20th century are relatively complete and their reprints are available in libraries. The most complete collection of coats of arms is Księga herbowa rodów polskich (The Coats of Arms Book of the Polish Families) by Juliusz Ostrowski dated late 19th century, but unfortunately the work remained unfinished. However, in heraldry a private initiative could not effectively substitute a state institution, because, for one reason, human life is short.

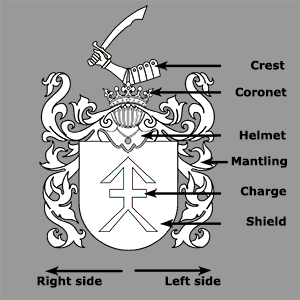

A coat of arms has a certain structure based on history and practical usage.

The main part of a coat of arms is called charge (godło). They were derived from ancient signs of ownership, seals, monograms that were depicted on banners in battles. In Polish heraldry, a charge usually depicted a weapon (for example, sword, arrow), an animal (lion, horse, deer, ram), agricultural tools (horseshoe, rake, sickle), plants (rose, oak), celestial bodies (crescent, stars), elements of architecture (gates, walls), different versions of crosses (Maltese, Greek, Latin) and – more common in Western Europe – heraldic figures (ordinaries): fesses, pales, bends, chevrons, piles and so on. There were also parts of human body (legs, hands, heads), monograms and many other images and objects. Charge was meant to be a graphically simplified and stylized image without perspective and shadows. However, it is astonishing how often these principles were ignored. Coats of arms were made by rural artisans and, at times, a hawk on a shield looked like a hen, a horseshoe did not differ from a crescent, and a sword from a cross. One can look with envy at graphically perfect German or French coats of arms, but it should be recognized that in the Polish heraldry, somewhat provincial, the form never dominated the content.

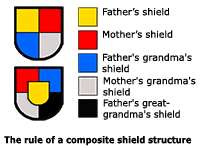

Charge must have a background. In coats of arms the background (field) is presented by a shield (tarcza) of a certain colour. The form of the shield depended on a historical period. When it was used as a defensive weapon, it bore a coat of arms. Later it became a conventional armorial background that resembled a shield and, at times, transformed into a decorative, quaint cartouche or simply a colorful field. Therefore, for a coat of arms essential was not the shape of a shield, but its colour and vertically, horizontally or obliquely divided zones on it. In some coats of arms, shield’s colour itself served as a charge. A divided shield could be a result of several coats arms merging in one. The fields of a divided shield (divisions) had certain order, degree of respectability and significance. When studying description of coats of arms, one should remember that heraldic sides of a shield are determined by its holder’s viewpoint, hence, the right side of a shield means the right-hand side of a knight facing us.

Composite shields most often represent genealogy of a particular person. Separated divisions are coats of arms of the ancestors, and only the central (heart) shield – and in its absence, the upper right division – represents a coat of arms of a family. Such coats of arms are used on gravestones, in private documents, most commonly among aristocratic families. Such coat of arms belongs to a particular member of the family – a deceased person, owner of the document or real estate. When it was depicted as such in a document conferring aristocratic title, it was inheritable, although with each next generation it was losing its relevance.

A charge on shield is the simplest, most generalized representation of a coat of arms.

In heraldry, the number of colors, that is, tinctures, is limited to metals (argent and or, that is, bright white and yellow), colours (gules, azure, vert, sable, purpure) and furs (ermine, sable, belette). Later these main tinctures were supplemented with corporel, d'acier and naturel ones. A conventional graphic system (hatching) is used to reproduce colors on stamps, statues, black and white drawings. It’s essential to know it when studying old armorials.

A helmet (hełm) topped with a coronet rests upon shield. In Polish heraldry, the shape of the helmet is arbitrary in general, given it is a close helmet. The coronet is most often of a nobleman type, i.e. with three fleurons and two pearls. In this respect western heraldry rules are clearly regulated and exceptionally strictly applied. Therefore, some Polish coats of arms of the foreign origin have other than coronet headgears. Rarely used are rank coronets (baron's coronet – with seven pearls, and count's coronet – with nine pearls), as well as princely mitres.

On a helmet topped with a coronet there is a crest (klejnot). This is a part of the coat of arms fixed on the top of the knight's helmet, visible from afar, greatly elevating the figure of the warrior, also identifying him despite a closed visor, and intimidating the enemy and frightening the enemy’s horse. Often a crest is a copy of the charge on shield, sometimes placed between horns or wings; at times it was an old, obsolete charge, or a character mentioned in a family legend. On many coats of arms, a crest is a bunch of peacock feathers (“peacock tail”), typical only to Polish heraldry, or ostrich feathers of a certain amount (usually three or five), most often argent (white). Some coats of arms do not have crest, coronet or helmet.

A decorative, optional element of a coat of arms is mantling or labrequin (labry), or a kerchief turned into a luxurious piece of cloth with partially or completely symmetrical ornament covering a helmet, which originally served to protect its bearer against the scorching sun and was especially effective when watered. This small but useful scrap of cloth turned into a decorative frame of a coat of arms, became bigger surrounding shield, outshining its main elements by its assertiveness and wealth. Colours of mantling depend on the colour of the coat of arms: the top corresponds to the colour of the shield, the bottom to the metal of the charge or its most important part. When shield is vertically (or horizontally) divided in two divisions, colours of the mantling of the right side correspond to the right (or upper) division of the shield, the mantling of the left side reflect the left (or lower) division of the shield. When shield is divided into more than two divisions, there are no strict rules determining the colour of mantling. Mantling of some coats of arms are described in ennoblement papers and in those cases mantling’s colours may differ from general rules.

Ornamental elements of coat of arms also include supporters (trzymacze), i.e. animal, human or mythical figures holding shield, fur-padded pallium covering coats of arms, a motto on a sash under a coat of arms. These embellishments were attached to coats of arms by appropriate diplomas as ennobling additions to an old coat of arms, most often issued together with conferring an aristocratic title.

A period when Rzeczpospolita was crossed off the political map of Europe is a different story worth of a separate note.

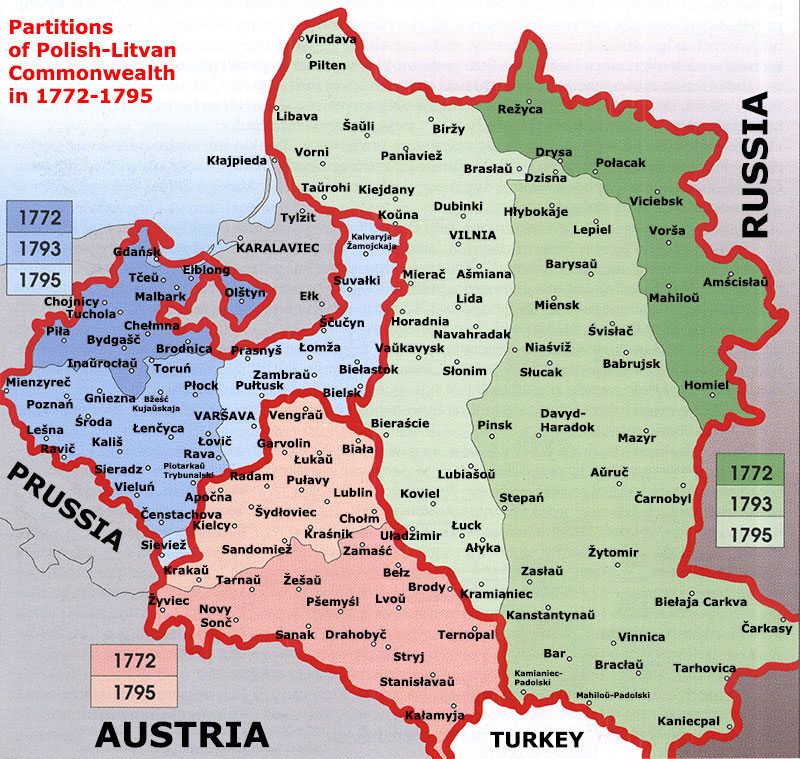

In August 1772, Russia, Prussia and Austria made the first partition of Rzeczpospolita. Over one-third of the population and almost one-third of its land came under control of neighboring monarchies. The process of extermination of Rzeczpospolita, or the Commonwealth of the Two Nations, once powerful state during the reign of the Piasts and Jagiellons, lasted until November 25, 1795, when, after the third and final partition Stanisław August Poniatowski, the King of Poland and the Grand Duke of Litva, renounced the throne. In these 23 years, when Rzeczpospolita was gradually killed, created were many new coats of arms of the Polish and Litvan nobility [pl]. At the same time in Vienna, Berlin and St. Petersburg three foreign monarchs established rules for checking the social status of their new subjects.

725 thousand square kilometers of the former Commonwealth was home to 12.5 million people, about 1.2 million of whom were nobility.

The nobility estate, which for centuries relied on its strength and independence and now under new rule struggled to get all available privileges, completely lost its status. Its legal position was unfavorable. Since in Rzeczpospolita, as mentioned before, there was no state institution registering nobility, it was often very difficult to confirm one’s noble origins. The impoverished nobility – and it was the overwhelming majority, especially in Mazovia, Podlachia and Litva, and also in the south of Poland – regarded documents with scorn and intolerance, which was well described by Mickievič in "Pan Tadeusz". Small wooden mansions were often destroyed by fires, as were manors of parish archives. Specifics of Polish heraldry that allowed using one and the same coat of arms by numerous families resulted in that coats of arms ceased to be distinctive family insignias. For that reason, they were often forgotten altogether. Signets, quite a rare possession for the "impoverished nobility", were used by nobility rather lightly, lent to or from neighbors when there was a need to go to court or another official purpose, giving little attention to whether the coats of arms depicted on them were similar to their own ones.

The rule of the new monarchies was far from democratic freedoms of Rzeczpospolita; their nobility was formalized, its noble origins were documented and approved by relevant official institutions. Even desire of the new rulers to reconcile with the key class of the occupied territories could not entail changes of the basic legal principles organizing state elites.

After the occupation, the Polish and Litvan nobility became nobility of a non-existent state with doubtful or unconfirmed by official documents authenticity. It is worth recalling that in Rzeczpospolita indigenats were granted very reluctantly, and the process of proving foreign nobility was very scrupulous. In this regard, demands of occupation authorities with respect to new subjects seem understandable and justified. The problem was that they used these procedures for discriminatory and political purposes. A proven origin did not secure restoration of the former social status.

Occupation authorities used very similar verification criteria: ennoblement diplomas (acts), occupation, land tenure, diplomas of officers, credence of ambassador. In general, meeting one of these criteria was sufficient. The real difficulty was to prove with documents continuity of generations.

In various occupation regimes, verification matters were dealt differently.

Under the Prussian occupation, legitimation was the most loyal because of the distinct difference of the nobility from the rest of the population, both in terms of wealth and education, and their way of life. The procedure was simple and carried out by a professional official. However, nobility that belonged to a wealthy class was obliged, in one form or another, to sign vassal or fiefdom letters declaring their loyalty to the new ruler. In dubious cases, it was necessary to prove that the family for at least last hundred years had been recognized as noble, which was tantamount to obtaining certification of nobility. Advantageous was possession of a well-known, recognized coat of arms, which minimized the number of applications introducing changes to coats of arms during legitimation process, which in the Prussian occupied territories were not as widespread as in others. Territories with a large number of petty nobility in Mazovia and Podlaсhia did not manage to get under the Prussian legalization, as in 1807 they were transferred to the Duchy of Warsaw and then under the jurisdiction of Russia.

In the Austrian occupied territories – very densely populated, with a large share of fragmented land estates – legitimation process lasted for many years and did not cover all nobility. A special commission created for this purpose and composed of five distinguished representatives of aristocracy turned out to be of little use, and since 1782 the city and district courts were responsible for legitimation, and in 1783 it became a responsibility of the Department of Estates of the Galician Sejm, an institution which since 1788 was headed by the Governor of Galicia. The department kept so-called šlachta metrics. Since 1817, recognition of a noble origin was an expression of the emperor’s favor. In the Austrian occupied territories, quite often ancestral coats of arms had been lost in time, so there was a large number of modified coats of arms submitted under legitimation procedure, drawings of which were based on oral family legends. Descendants of senators, voivodes, hetmans and high-ranking officials of Rzeczpospolita had the right to claim the title of a count. The title of a baron was granted to descendants of district officials. Title acquisition required a fairly high payment and depended on the emperor’s decision. This was because a new coat of arms was presented in a new noble frame. A significant part of the Polish aristocracy came from nobility of those occupied territories, since only there title acquisition to large extent depended on past merits of the ancestors.

Russia captured over 60 per cent of the territory of Rzeczpospolita, with almost half of its population. In the Russian occupied territories political character of nobility legitimation, especially in the former Grand Duchy of Litva and Volhynia, was most vivid. Legitimation was carried out by the Department of the Heraldry of the Governing Senate and the Heraldry Department of the Congress Poland (1836-1861) through provincial nobility deputies' assemblies. Part of nobility, the largest one, that did not own land, was ranked as peasants or petty bourgeois. There were also new estate surrogates - "odnodvortsy" (owners of single farmsteads) and "free ploughmen". Under this occupation regime, there was the largest number of coats of arms that were groundlessly taken from armorials or modified. Nobility deputies' assemblies in the territories of the former Rzeczpospolita, dominated by the Litvan nobility, were favorably disposed towards applicants, and Russian authorities did not attach importance to coats of arms because historically the Russian nobility didn’t have coats of arms. Legitimation continued as long as until 1917.

In this period new coats of arms – variations of known ones – appeared, and the only reason of their existence were diplomas of the royal heraldry. For many families, they were the only documents proving their family insignias.

A significant number of coats of arms which appeared in the occupation period were coats of arms associated with appropriation or confirmation of aristocratic title. Owners of extensive estates scattered throughout the territory of the former Rzeczpospolita sought to boost their prestige with a title of a count or a baron. To confirm the title one had to go through an established procedure in each of the occupations. For that reason, many aristocratic families had several versions of their coats of arms confirmed by different occupation regimes.

The greatest number of new coats of arms in 1772-1918 came out as a result of ennoblements obtained by representatives of non-nobility classes. In this regard all empires used similar policies and principles. Ennoblements were awarded to officers and officials for a certain length of service (each occupation had its own standards) in appropriate rank. Nobility was also granted when receiving certain orders and awards especially military ones.

In addition, the monarchs granted nobility to people who had earned it serving the royal court, the state and society. As a rule, such ennoblements were granted along with aristocratic titles.

Cases of granting title of a count by the Holy See for charity and services to the Roman Catholic Church were quite rare at that time and they had no influence on the increase of coats or arms total number.

A special group of coats of arms represent ennoblements and titles of the French Empire. Many officers of the two Polish-Litvan legions of Napoleon Bonaparte's army became cavaliers, barons and counts of the Empire for their valor. Design of their coat of arms is characterized by certain ideological discrepancy – helmets topped with a coronet were replaced with republican, antimonarchic berets. At that time in the Duchy of Warsaw several persons passed through ennoblement procedure. After the Congress of Vienna ennoblements and titles granted by the French Emperor were repeatedly confirmed by new rulers. But it was quite often when owners of those coat of arms or their descendants returned to using their more ancient ancestral coats of arms.

Completeness of information on ennoblements conducted under different occupation regimes varies greatly. New Prussian coats of arms, though not numerous, are an integral part of the heraldic heritage of the German Empire. There is information about the majority of Austrian ennoblements. This occupation regime had a separate administrative unit in the form of the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, which archives also survived and have been published.

Situation with the Russian occupied territories is the worst. Most of the archives of the Kingdom of Poland in Warsaw were burned during World War II, while during the Soviet period Saint Petersburg and provincial archives were inaccessible to researchers and, to this day, are waiting for their discoverers.

Based on: T. Gajl. Herbarz polski od średniowiecza do XX wieku - Wstęp

Prepared @ translated by J. Lyčkoŭski

* Hereafter authentic name of medieval Belarusian State (the historical Lithuania). Read more...